Immigration policy used to be a bipartisan issue, but now it is one of the most divisive in American politics. This study explores how lawmakers’ behavior changed as immigration became a party-defining issue–and what that means for the way Congress represents the foreign-born population. Using immigration bills in the House of Representatives from 1983 to 2014, email newsletters from 2010 to 2020, and data on district characteristics the authors ask: Do representatives still respond to immigrant populations in their districts, or does representation depend on which party wins the seat?

Expectations

The authors set out to discover whether polarization on this issue changed the mechanism of representation. They expect that as the issue polarizes, immigrations positions will depend more on party than on the size of the foreign-born population in the district, and that the effect of the foreign born population will occur via the electoral mechanism – influencing which party holds the seat – rather than by lawmakers’ in the same party holding positions that align with district characteristics. They also expect that under polarization the constituency effect will shift to predicting how active lawmakers are on the issue, rather than their positions.

Methodology

To test their expectations, the authors use three sources to measure lawmakers’ positions on immigration: floor speeches, email newsletters, and an original data set of immigration-related bills. Then, using regression models, they estimate the relationship between district demographics and legislators’ positions.

Key Findings

The Partisan Divide Has Grown

Figure 1 reveals the dramatic divergence of immigration positions over time between the two political parties. While Republicans move sharply toward anti-immigration positions, Democrats grew more supportive of immigration. This finding suggests that immigration has become a core partisan issue in U.S. politics, leaving little room for bipartisan collaboration.

Figure 1. OLS coefficients of republican partisanship on pro-immigration positions. Figures report coefficients on Republican partisanship from OLS models estimate for each dependent variable in each Congress. Y-axes are on different scales.

The Mechanism of Representation Has Changed

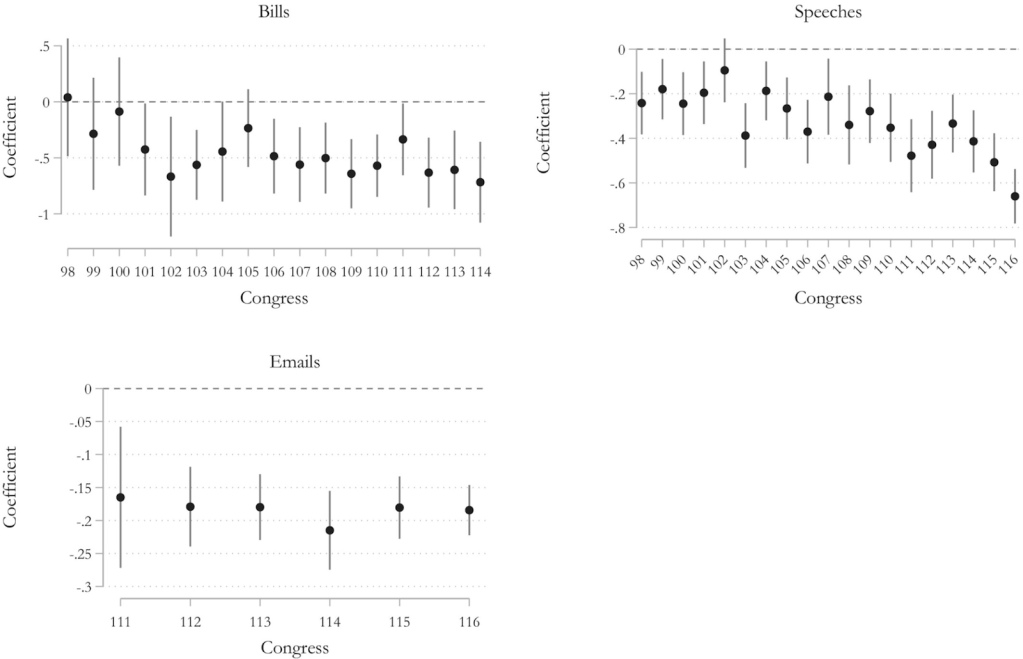

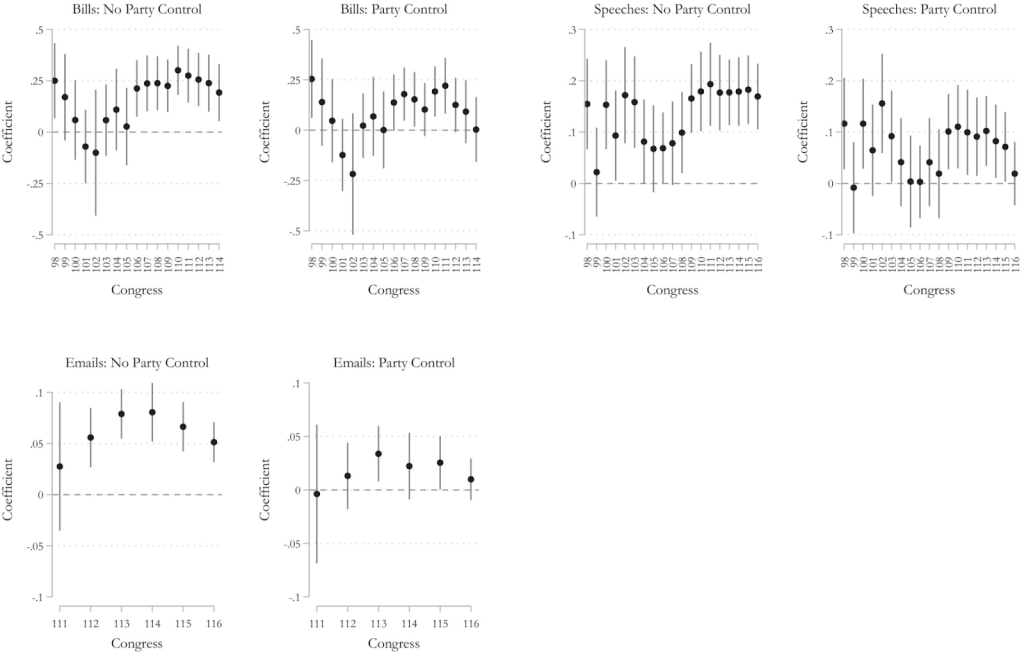

Figure 2 suggests that immigrant populations still matter–but indirectly. Instead of shaping individual lawmakers’ positions, foreign-born constituents hold more influence on which party wins the congressional seat itself, in part because they have become a more Democratic constituency. While Democrats representing districts with larger foreign-born populations. The correlation between the foreign-born population and legislators’ positions has actually become stronger, but it now passes through partisanship rather than dyadic responsiveness.

Figure 2. OLS coefficient of foreign-born percentage (10-point increments) on immigration positions over time.

Asymmetrical Activism

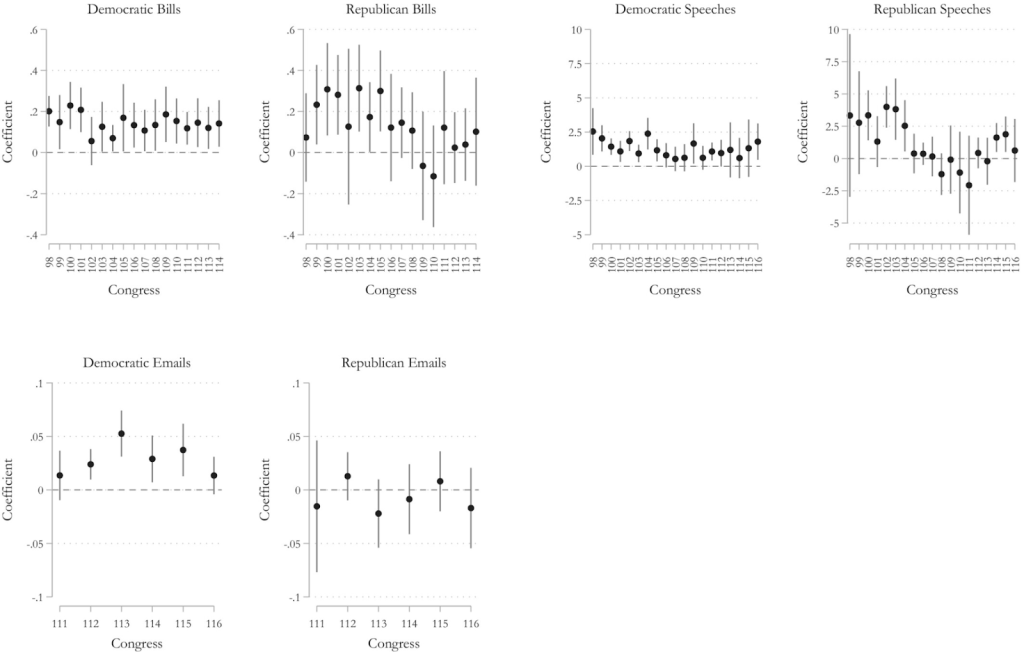

Figure 3 shows that Democrats with higher shares of immigrant constituents tend to be more active on immigration (e.g., sponsoring bills, giving speeches, and mentioning immigration in emails). On the other hand, Republicans show no such trend. Instead, the most conservative Republicans are the most active on immigration. For Democrats, the immigration agenda is set by representatives of immigrant communities, while for Republicans it is set by the conservative wing.

Figure 3. Effect of percentage foreign born on the number of actions by party.

Why It Matters

Polarization has transformed how representation works. This article explores how party sorting reshapes legislative behavior and agenda-setting on immigration. For immigrant communities, influence now depends on influencing which party wins the election. The authors insist that future research should explore whether similar patterns occur on other party-defining issues, and how local advocacy strategies adapt in an era of deep national divides.

Read the original article in Policy Studies Journal:

Cayton, Adam and Lena Siemers. 2025. “The Dynamics of Constituency Representation on Immigration Policy in the U.S. House.” Policy Studies Journal 53(2): 480–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12579.

About the Article’s Authors

Adam Cayton is an associate professor in the Reubin O’D. Askew Department of Government at the University of West Florida. His research focuses on legislative representation. He received a Ph.D. from The University of Colorado – Boulder, and a B.A. from The University of North Carolina at Asheville.

Lena Siemers is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Global Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell. Her research focuses on migrant and refugee studies. She received a M.A. from the University of West Florida and a B.A. from the University of South Alabama.