by Weixing Liu, Liang Ma, Xuan Wang, & Hongtao Yi

While policy diffusion based on learning mechanisms has received extensive scholarly interest, this literature has at least two limitations. First, policy learning is usually identified through indirect evidence, such as geographical proximity or successful policy innovations adopted in other jurisdictions. Second, measures of policy learning are used without considering how they interact with other factors.

To address these limitations, our study measures policy learning through field learning conducted by local government officials, using the case of Chinese local financial subsidy policy for new energy vehicles (NEVs). Site visits from local government officials offer a direct mechanism of policy learning by enabling policymakers to exchange strategies and information with peers about the “know-how” of policy implementation.

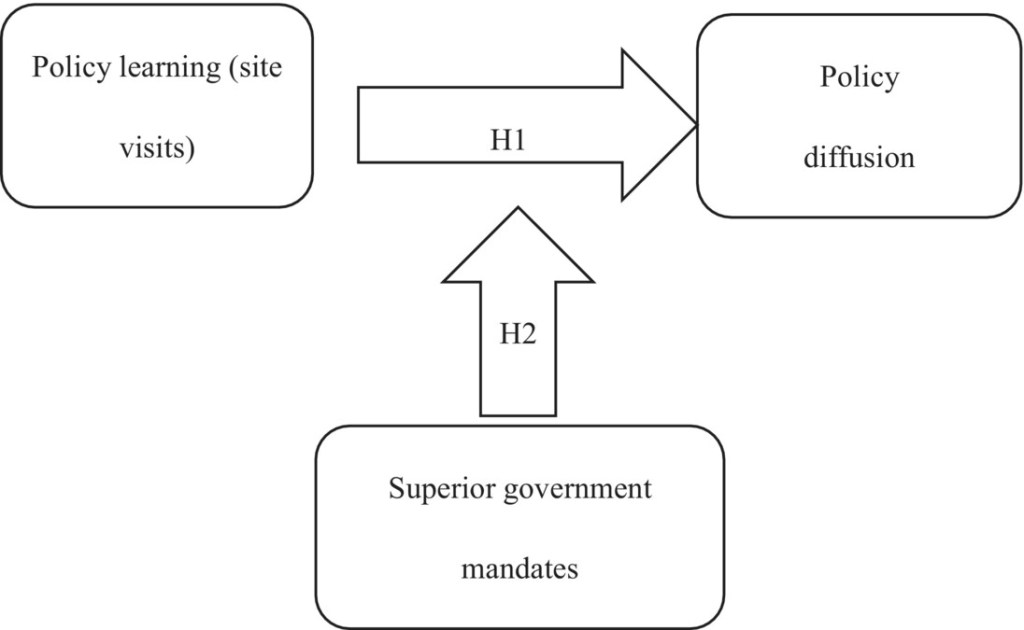

H1: When city i initiates policy learning from city j, policy innovation is more likely to diffuse from city j to city i.

We also examine the moderating effect of top-down mandates on . While governments learn from each other, they are also embedded in a multi-level regime, in which higher level authorities mandate or incentivize subordinate governments to adopt policies they favor. If the top-down signals are strong, peer-to-peer learning may be weakened.

H2: The adoption of the focal policy by the superior government will attenuate the impact of policy learning on policy diffusion across jurisdictions.

Figure 1. The theoretical framework and hypothesis

To test these hypotheses, we collected data on the adoption of NEV policies in 282 cities between 2014 and 2018. The key independent variable captures interlocal learning between cities. To identify site visits, we searched for the keywords of “visits and learning” and “learning and exchange” on official websites and official papers in the cities. To examine the role of top-down mandates, we included a variable indicating whether NEV policies had been adopted by the superior government. Finally, we controlled for other horizontal diffusion mechanisms.

Using a directed EHA method based on a logit model, we find that the direct information exchange between local governments can significantly promote the diffusion of the NEVs’ local financial subsidy policies between cities. However, the purpose for the site visit has different implications on the diffusion of the policy. Empirical results indicate that compared with policy learning within public services, urbanization, government management, and cooperative projects, learning in the field of economic development, which is more related to the NEVs financial subsidy policy, can significantly promote the diffusion of policy innovation.

Consistent with H2, the results also show that policy behavior signals from a superior government can replace or decrease the impact of interlocal policy learning on policy diffusion. Lastly, the research shows that the level of authority of the government official who conducts the site visit plays a role in the adoption of the policy. That is to say, the more authority that the visiting government official has, the higher the chance of adoption of that policy in the other city.

In summary, the findings indicate that policy learning plays a crucial role in policy diffusion, and governments can leverage site visits and other learning approaches to facilitate policy adoption. While conventional information channels help policymakers to learn about emerging policy innovations, face-to-face interactions may be more influential in policy diffusion. Particularly for leading government officials with scarce attention to specific policies, their dedicated site visits could boost policy learning and then policy diffusion and spread.

You can read the original article in Policy Studies Journal at

Liu, Weixing, Liang Ma, Xuan Wang and Hongtao Yi. 2025. “ Interlocal Learning Mechanisms and Policy Diffusion: The Case of New Energy Vehicles Finance in Chinese Cities.” Policy Studies Journal 53(1): 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12576.

About the Authors

Weixing Liu is an assistant professor at the School of Government, University of International Business and Economics. His research focuses on policy process, environmental policy, and networks.

Liang Ma is a professor at the School of Government at Peking University. His research interests include digital governance and performance management.

Xuan Wang is an assistant professor at the National School of Development at Peking University. His research interests include tax policy, China’s economy, and policy innovations.

Hongtao Yi is a professor at Askew School of Public Administration and Policy at Florida State University. His research interest focuses on network governance and environmental policy.