Governments around the world use local content requirements (LCR) to boost domestic industries by requiring renewable energy projects to use a certain share of locally-made components. The idea is simple: create jobs and build local supply chains. But the results have been mixed—some countries became major exporters of wind and solar technology, while others struggled. This article asks: Does the way these rules are designed explain why they succeed in some places and fail in others? To find out, the author uses Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) to look for patterns in how different policy features and economic conditions combine to produce success.

Hypotheses

The author tests three hypotheses:

- Policies work best when countries already have strong technological capabilities.

- Combining LCR with other tools (e.g., financial incentives, renewable energy targets) helps in tougher economic environments.

- No single factor guarantees success; it’s about the right mix of design and context.

Methodology

The author analyze 27 LCR policies in wind and solar energy across 19 countries from 1995 to 2017, using fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) to uncover patterns. The research examines how policy design elements (e.g., restrictiveness, policy mixes, and targets) interact with the political economy (e.g., investment conditions, economic complexity). Success was measured by whether a country’s exports of wind and solar components grew four years after introducing LCR. The analysis looks for combinations of conditions that consistently led to positive outcomes rather than a one-size-fits-all solution.

Key Findings

Flexibility or Strong Capabilities Are Essential

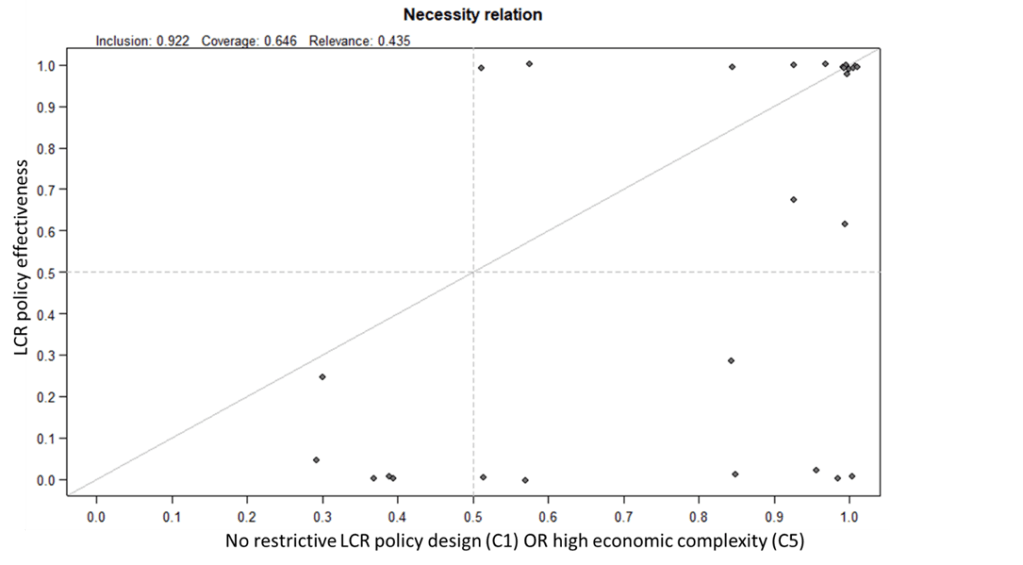

Figure 1 shows that either a flexible LCR design or a country’s high economic complexity must be present for a policy to be successful. While countries with advanced technology sectors can handle stricter rules without harming investment, those with limited capabilities need more lenient requirements to attract investment. This finding supports Hypothesis 1, demonstrating that there is no universal approach—what works in China or Spain may fail in India or Argentina. The author therefore argues that successful policies must be tailored to local conditions and political-economic contexts.

Figure 1. XY-Plot of the necessity relation between (C1 or C5) and LCR Effectiveness.

Policy Bundles Make a Difference

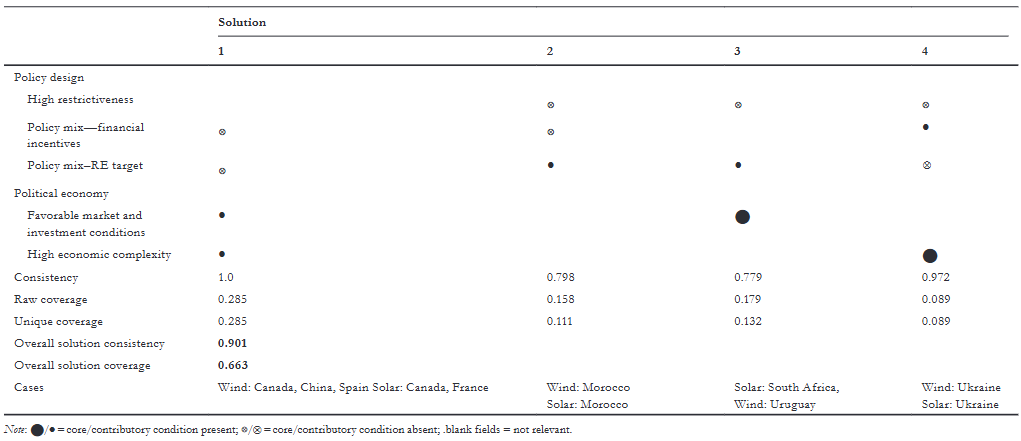

In countries with weaker investment conditions or limited technological capacity, LCR only worked when paired with financial incentives or renewable energy targets (Table 1). These extra measures help attract investors and signal future demand, giving local industries time to grow. This finding supports Hypothesis 2, underscoring the role of strategic policy bundling for green industrial success. Furthermore, the author explains, while simple rules can work in supportive environments, complex policy mixes are essential in challenging one.

Table 1. Sufficient conjunctural patterns of policy design elements and contextual factors for LCR policy effectiveness.

Why It Matters

This article reveals that smart policy design matters. LCR effectiveness depends on tailoring rules to local conditions and, when needed, combining them with other supportive policies. This research challenges the idea of universal design principles and shows that success comes from the right mix of tools and context. Future studies should explore how these patterns apply in other sectors and dig deeper into why some policies fail. Scholars could also improve data on granular design features like technology transfer requirements. For policymakers, the message is clear: design green industrial policies with flexibility, consider context, and do not rely on a single instrument.

Read the original article in Policy Studies Journal:

Eicke, Laima. 2025. “Does Policy Design Matter For the Effectiveness of Local Content Requirements? A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Renewable Energy Value Chains.” Policy Studies Journal 53(3): 604–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12590.

About the Article’s Author

Laima Eicke is a Research Associate at the Research Institute for Sustainability in Potsdam. Her research focuses on the international political economy of the energy transition, value chains of renewable energy technologies and hydrogen in particular as well as on green industrial policies. She is a former Associate and Research Fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at the Harvard Kennedy School and worked at the German Corporation for International Cooperation (GIZ), the Germany Ministry for International Affairs, NGOs and in consultancy.